Goodbye Tata Madiba

All day, the television channel has been set to news. That’s never a good sign.

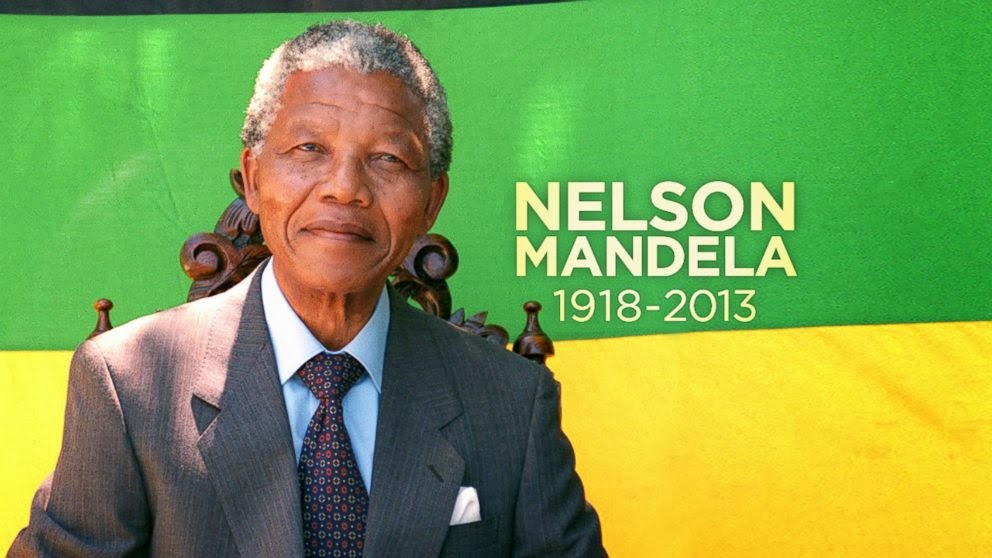

We’ve been watching a nation mourn. Our Tata (grandfather) has died. Nelson Mandela has finally closed his eyes for the final time.

I met him when I was eighteen. We were high school debaters on tour and literally debated our way into his home. He entertained us there for forty-seven minutes. That’s a long time. I vaguely remember that he had to reschedule a meeting with Kofi Anan, the then head of the UN, in order to share a cup of tea with us. He loved children. And he loved the country he called home.

This death happens at a time when I was feeling particularly low about being South African. Recently I have lost a friend/colleague through a murder and the freedom to run in my neighbourhood because of rape. I wasn’t feeling all that great about our beloved country. But then something like this happens and shifts perceptions back to where they once were.

I was raised in a very traditional community (read: fairly racist.) It was a mining town, as I have mentioned before, and the labourers, because of apartheid laws, had to live out of town and commute to the mines. The quickest route to the mine-shaft close to our house was literally right past our house. It became such a problem that eventually our not-so-liberal town clerk put a wall up at the end of my street, essentially creating a cul-de-sac sans a turning circle. Anyway, I digress. Come 1994 and the first free and fair election is taking place in South Africa. Black people are allowed to vote for the first time.

White people are fleeing the country like rats on a sinking ship, certain that the ANC and Mandela are going to throw us to the dogs. And what was I doing? Well, I was campaigning for Mandela, of course. I stole the VOTE ANC posters from around the block and hung them on our street pole. I waved a new South Africa flag with Mandela’s face in the corner from my window and hung one proudly on my door. Fortunately, my family have never been bigots of any kind. If I had been eligible to vote for him, I would have, but instead, I went on a one-woman(child)-mission to persuade all the racist, traditional neighbours that Mandela was the way forward for our nation.

The ANC didn’t actually need their votes. Being a country oppressed for so long, the ANC won the election in a landslide, its voting contingent expressing their voice for the first time in their lives. But again, I digress.

Placing these posters up on my front lawn suddenly turned my home into a picnic spot for mine workers moving from the taxi rank to the shafts, or returning home. We had a garden tap that was useful if they wanted a drink or a quick wash. We had a few trees under which they could find shelter from the harsh Free State summer sun. Needless to say, my neighbours were horrified. That was far too many black people too close to home.

Placing these posters up on my front lawn suddenly turned my home into a picnic spot for mine workers moving from the taxi rank to the shafts, or returning home. We had a garden tap that was useful if they wanted a drink or a quick wash. We had a few trees under which they could find shelter from the harsh Free State summer sun. Needless to say, my neighbours were horrified. That was far too many black people too close to home. I loved it. My parents tolerated it, (people picnicking on their lawn,) for my sake.

Nelson Mandela became president in April of that year and I felt I had helped him get there. Even in my small way.

When I met him four years later, almost to the day, I was blown away at what a giant he was. In my eyes, as with all our heroes of childhood, he had always seemed larger than life, but I kind of expected him to be about my dad’s size. He wasn’t; he was much, much bigger. His hands were like badminton bats and his arms were long enough to drape a chair arm. His presence was mirrored in the sheer volume of person that physically welcomed us into his home. Of all the things about him, that struck me first.

The second thing that struck me about the man was that he was incredibly gentle. His spoken voice, partly due to his already-then aging body, but also because of his nature, was soft and soothing. You felt like you were speaking with a grandpa and I understood clearly why so many South Africans referred to him as Tata. His lap was large enough for many grandchildren, and his voice certainly would have told a beautiful bedtime story.

But the final thing that struck me about him was his respect for the individual. There must have been about fifteen of us there that day. We weren’t allowed to bring in any cameras and it was before smartphones, and so there was little evidence that we had even been there. But he signed, on the presidential stationery, a personal note for each of us. He asked us each what we were planning to be when we grew up and then wrote a note to encourage us. Like the story in the beautiful film Invictus, where Mandela focused on learning each player’s name of the Springbok team, in his home, our president looked each one of us in the eye, asked our name and then wrote us a note. We were children. He was the president. It blew us all away.

My note read: “To one of our future leaders.” Back then, well, I wanted to change the world. When I took it out today, mourning his passing, I had to ask how I am living up to those ambitious eighteen-year old’s expectations.

You see, I wanted to be a politician or a lawyer, or a writer who made the world stand up and take notice. I wanted to dominate in my field of expertise, (yet to be determined) and make my mark on the world with paw prints as large and everlasting as he had. He was a role model and someone to exemplify. And initially, looking at that little card with the big message from an even bigger man, I felt I had let down the cause.

But then I started reading some of the quotes doing the rounds as we remember Tata Madiba. I realised that I haven’t fallen short of those early ambitions, but rather, altered the small course of history of which I am the captain.

“For to be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.”

I will teach my children that they need to respect each and every person they meet. Just as a great leader could once look me in the eye and make me feel as though I was the most important person in the room, they should do the same, even for folks who are ‘lesser’ and even for other children. They have been born into a world where very little needs to worry them. A childhood of privilege and opportunity. A childhood of freedom. We need to celebrate that by ensuring the freedom and respect due to those we meet. Which ties in to the next quote quite nicely.

“No one is born hating another person because of the color of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.”

My children will be taught to love. They will also be taught to persevere.

“The greatest glory in living lies not in never falling, but in rising every time we fall.”

“I learned that courage was not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it. The brave man is not he who does not feel afraid, but he who conquers that fear.”

They will be helped to be courageous. Especially when it comes to doing right, speaking the truth or expressing themselves. I need to show them this by doing it myself. Daughters, especially, need to be taught that it’s okay to have a voice, an opinion, a cause and a purpose.

“Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.”

As a former teacher, this quote is often on my lips. Not only can I ensure that my daughters gain a good education, but I can help those less fortunate attain this as well. Perhaps not by paying school fees, but by donating time, books and efforts in order to ensure an attitude of learning. For after all,

“A good head and a good heart are always a formidable combination.”

Nelson Mandela was a true hero. As a statesman, he had ideas that were contrary to those expressed by so many of his followers, yet he stood his ground. The shoes he leaves empty in his passing are so enormous, it would take a team of the current ANC leaders to fill them. I pray that one day they do.

And as for that eighteen year old girl who told him confidently that I was going to change the world, maybe one day in my own right, I will. But in my home, where I am a leader now, it is my duty to raise my children embracing some of the ideals expressed in these words. I pledged, in 1998, to be a leader, and so this is what I would like to lead them to do. Have their own ideas. Think about things properly. Explore all avenues for opportunities. Make the most of each day. Most importantly, to be kind to all people, respectful of all creeds and colours and to value their freedom and education.

Why should I do this? They are after all, ‘only’ children, my little girls?

Well, because Nelson Mandela was once ‘only’ someone’s son.

Comments

Post a Comment